This is the fifth project in the A Shrinking Feeling lineage. Like most of the previous entries in the series, this is a procedural music program intended for public exhibition. It takes about three minutes to "warm up", and should provide an interesting listening experience for up to an hour or so. I highly recommend listening to this through headphones or dedicated speakers, since the music is very texturally complex and doesn't do well on laptop or phone speakers.

Controls

- Hit Pause if you need to, and then hit Play again to resume.

- Restart will start the piece over from the beginning.

- Fullscreen does what you'd expect — hit esc on your keyboard to exit.

- Sound Check plays a random sample from the system, useful when I'm setting up for a public exhibition.

- The rest of the buttons are just to help me debug the system when something goes wrong.

How It Works

Diminished Fifth is written in ClojureScript, and runs in the browser using the Web Audio API. The simulation is mostly deterministic — each run will be just slightly different. There's a very small pool of pre-written melodies used as source material, so the musical result will be very self-similar at times. As I continue to work on the project, I'll be expanding the breadth of sounds and moods produced.

No, Really.. How Does It Work?

You're sitting down? Have a drink? K..

Let's skip over the tedious bits about setting up a Web Audio context, programming reverb filters, and other necessary-evil plumbing (@ me if you want to learn about this gunk). Instead, here's the skinny on what in the fresh hell is arriving at your ears. I'll casually use music and programming terminology, so if this is too murky for you let me know and I'll clean it up.

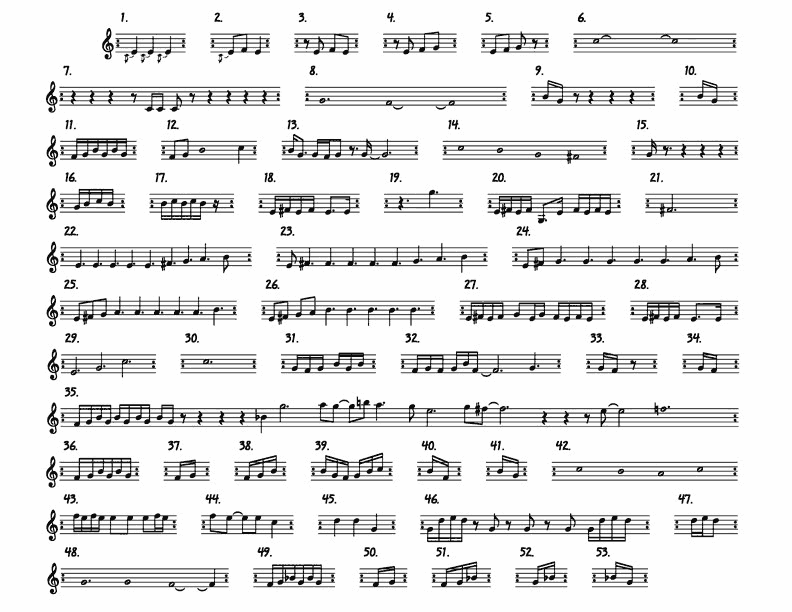

There is a pool of about 15 melodies — little fragments of written music. (They're so small, and so often recurring, that motif is probably a better term than melody.) These melodies were written carefully so that they can be transformed in tempo, shifted out of alignment, and combined together in almost any fashion, and yet the result should still be sensical. Perhaps a bit like the score to Terry Riley's In C. (Here's my favourite rendition.)

In C, © Terry Riley 1964

There is a pool of about 81 sound samples — recordings of an individual note played on an instrument. They were extracted from a bunch of different songs, and especially from Above Genus, Below Order. (Note that the songs on my albums generally aren't sample-based, but rather are multi-track recordings of me playing the instruments, so I had to be a bit surgical to pull out clean single notes from recordings of longer musical phrases.) All of the samples are tuned to the same musical pitch.

If the system needs to play one of the samples in a D rather than a C, it just plays the sample a bit faster. How much faster? I'm using Pythagorean tuning (with the octave comma). In the case of C to D the ratio is 9/8, so I play the sample at 1.125 times the normal rate.

When the program runs, we generate a bunch of "players" for our "orchestra". Each player is assigned a melody to play, and a sound sample with which to play the melody. Like a real orchestra, they play their musical part (melody) with their instrument (sample) in concert with all the other players around them. The harmonious whole is greater than the sum of its parts (we hope).

Next, the entire orchestra is placed into a time machine. In addition to conducting the orchestra, the conductor has their hand on a big dial that says "slower" on the left and "faster" on the right. As the audience is listening to the music, the conductor can reach over and start twisting the dial one way or the other. The passage of time experienced by each player seems normal enough — when they look at the other players, everyone seems to be playing together harmoniously. The passage of time experienced by the audience seems normal too — other audience members are coughing and checking their glowing screens at what seems like the usual rate. But the music, flowing out of the orchestra, out of the time machine, and washing over the audience… sounds sped up, or slowed down, like someone playing a vinyl record at the wrong speed. BUT! Here's where the analogy breaks down. Unlike a real orchestra in a time machine, or a real record player, when our orchestra speeds up or slows down, the pitch of the music doesn't change. (Because this is software and I can do what I want.) (Also because having the pitch change with the tempo would lessen the sense that this is meant to be listened to as real music, rather than as some sort of tech demo.) (Also because we'll handle pitch changes in a moment.)

The conductor's time dial doesn't have an upper or lower limit. They can keep cranking it slower and slower, and the relative passage of time will keep slowing down, half as fast as normal, and half again, and half again. Or the other way, faster and faster, seemingly without an end.

That's pretty wild, but it's not enough to make an hour's worth of interesting music. So, into this conceptual framework we pour a few other ideas.

After a player repeats their melody a certain number of times, they'll move up one octave. This "certain number of times" interacts in fun ways with varying degrees of relative difference between player-time and audience-time.

Another thing that can happen is that the orchestra can change key by a 5th. This happens once in an odd while, and you can trigger it manually by hitting the "transpose" button. To see what this sounds like, give the system about a minute to warm up, then click the transpose button once and listen to what happens for a few seconds, then click it again and listen for a few more seconds. Notice the effect this has on the graphs — you'll see the regularly repeating melody patterns get a bit jumbled when you transpose. Transposition is a dramatic effect, which is why it happens only rarely. Oh, why a 5th? Because by traveling around the circle of fifths, we get to visit all of the keys.

You're wondering why some players have squiggly graphs, and others only have these little orbs that fly from right to left. The squiggle players are melody players. The orb players are "percussive", and they follow a slightly different set of rules from the melody players. Percussive players don't have a pre-written pattern that they play. They have a chunk of logic that defines a system of rhythm, including notions like "triplets" and "ghost notes", built from arithmetic rather than pre-written music notation data. The percussive players are a recent addition, to help make the music feel more propulsive, so they're still a little under-realized. Bear with me.

Players can die. Players will die. It happens if they get too far away from the audience's time scale, or if they repeat their melody too many times and jump up too many octaves, or if they don't come to rehearsal on time. When players die, new players are created, with a new melody, a new sample, a new time scale, etc. This keeps the music interesting and continually evolving as you listen for longer stretches of time.

Unfortunately, when the conductor cranks the dial too far one way or the other, the music becomes incomprehensible because, alas, humans aren't comfortable listening to music with hyperdense or hypersparse structures (I've tried my best). So um… let's put each player in their own personal time machine. When they're first born, if they feel like the music they'll be playing will be too fast or too slow when it reaches the audience, they can hit a button to double or half their flow of time, to bring it back to being within a comfortable range. (I soothe myself by naively believing it also helps avoid floating point errors.) As crazy as this might seem, they can play at double or half (or four times, or a quarter...) the speed of the rest of the orchestra, and this does not destroy the sense of musical cohesion. If you're snapping your fingers to the beat of a song, you can snap on every 2nd beat just fine — and you can snap twice as fast, no problem. Most music is structured on a powers-of-2 series, and it's exceedingly rare to find a song that doesn't support being divided or multiplied by a power of two. (Here's a song where the first ~2 minutes are set in 7-against-4 — so no, prime number meters don't outright rule-out power of two transformation/combination.)

So, to recap, we have the entire orchestra speeding up or slowing down to wild extremes, but the individual players can counteract that difference when they are born, and at all times the sense of musical pitch is unaffected, except when it it's not. The music is harmonious, but at wildly warped and warping tempos, and yet cohesive because we were very careful about how the warping happens.

No, Like.. How Does It Work, Like If I Wanted To Make Something Like This Myself You Could Tell Me And Then I Could-

The code is up on HitBug.